Black History Unburied: Toronto Necropolis Beyond the Grave

The Necropolis Cemetery is home to some of Toronto’s most notable and somewhat notorious changemakers. It’s also home to some of the most important Black figures from the 19th century who laid their mark in building the city through their own contributions. What does the Necropolis tell us about their stories and their impact in the making of modern Toronto?

Contents

This story explores the Toronto Necropolis, one of the city’s oldest and first non-denominational cemeteries. In it lies a wealth of history that gives us a small glimpse into local history. From William Lyon Mackenzie, rebellion leader and our first mayor to publisher of the The Globe and Mail and activist George Brown, the Necropolis is the final home for those who made a huge impact in our city. It’s also the home to Toronto’s Black community of the 19th century, including some of the most notable Black leaders and community members who shaped everyday life in the growing city of Toronto.

This story was researched and written by Emerging Historian Jonsaba Jabbi (2023) under the Equity Heritage Initiative made possible by the generous support of our Tours Program Presenting Sponsor, TD Bank Group through the TD Ready Commitment.

Last updated: January 31, 2024

We’d love to hear your feedback. Contact us.

Why the Necropolis?

What does the Necropolis tell us about Black life in the 19th century?

Back in the 19th century, Toronto was segregated by class, religion and race. If you were born Anglican, you would go to Anglican school, marry an Anglican, raise your children as Anglicans as well as die and be buried in an Anglican cemetery. It would be the same for Catholics, Jews, and many others.

But what if you didn’t fit into those boxes? What if you were Methodist? Or a Baptist? What if you were Black? There’s a good chance that you would have been buried in the Necropolis. What if you were poor? Or a criminal who was deemed unworthy to be buried on sacred grounds? Anyone who would have been deemed mentally ill, sex workers, criminals or controversial figures would have been buried in the Necropolis. The cemetery is also home to individuals who belonged to smaller religious denominations, such as Methodists, who would not have had their own cemeteries to be buried in. Even if Black people were Anglican or Catholic, they would have been buried in the Necropolis rather than in other religious cemeteries due to the racism and discrimination they faced.

Toronto Crematorium Chapel, Toronto Necropolis Cemetery, September 19, 2023. Image by Oscar Akamine.

The collection of sculpture and Victorian buildings make it one of the most picturesque cemeteries in the city, with fine examples of High Victorian Gothic architecture in the fully restored cemetery entrance, chapel and office.

Mount Pleasant Group

Mount Pleasant Group website on Toronto Necropolis

The Black Community in 19th-Century Toronto

The Ward was home to many newcomers from around the world, including the Black community in 19th-century Toronto.

Today, Toronto’s Black population is over 440,000 people, making up 36% percent of Canada’s Black population as a whole. But, back in the 1830s and 1840s, the Black community was small and intimate at around 500 people. Although small, it was growing steadily with freedom seekers coming through the Underground Railroad. The majority of Black newcomers to the city settled in an area called St. John’s Ward, which was bounded by College, Queen and Yonge Streets and University Avenue with the main intersection at Bay and Albert Streets. Back then, it was considered one of the poorest neighbourhoods in the city. It was also home to an eclectic community of immigrants from Ireland, China, Italy, Eastern Europe as well as other Black freedom seekers making their way to Toronto.

Although most of the buildings that once made up the Ward were demolished in the 1950s and 1960s to make way for Nathan Phillips Square, today, St. John’s Ward is remembered as the Ward, Toronto’s first immigrant community. The Ward also holds special importance because of its legacy in relation to the Necropolis. Several members of the Black community who are buried at the Necropolis also lived and owned properties in the Ward. Today, there are barely any traces of the existence of the Ward apart from a few street names, but its legacy exists in the lives of the people who are resting in the Necropolis, including a couple who started Toronto’s first taxi company, making them one of the most prominent and successful Black families of their day.

Necropolis Cemetery, Winchester St, 1952. Image by James Victor Salmon, courtesy of the Toronto Public Library

About 35,000 African Americans came to British North America before the Civil War – artisans, barbers, seamstresses, hostlers, and other skilled workers gravitated to urban centres. Women, alone or with small children, found employment, while elderly newcomers relied on the African Canadian community’s support networks.

Karolyn Smardz Frost

The Ward: The Life and Loss of Toronto’s First Immigrant Neighbourhood (2015)

Thornton and Lucie Blackburn

Thornton and Lucie Blackburn, freedom seekers who came to Toronto through the Underground Railroad, became one of Toronto’s most successful Black entrepreneurial families.

After a long and hard journey escaping enslavement in Kentucky in 1831 and travelling via Michigan through the Underground Railroad, Thornton and Lucie (known then as Ruthie) Blackburn arrived to Toronto in 1834. As they built their new life in the city, Thornton took a job as a waiter at Osgoode Hall while Ruthie, who changed her name to Lucie as a sign of their emancipation, maintained their home and later worked alongside Thornton in managing their business affairs.

One day during his shift, Thornton overheard lawyers complaining about the city’s lack of public transportation while praising a new form of public transportation called the Hackney cab which was a success in London, England and had recently arrived in Montreal. Thornton obtained a pattern of a Montreal cab and commissioned Paul Bishop, one of Toronto’s most esteemed mechanics at the time, to build the cab for him. In 1837, Toronto’s first taxi company was born.

The taxi company was called “The City.” The Blackburns’ horse-drawn buggy cab held up to four passengers and was a known fixture in Toronto’s streets. It was red and yellow which served as an inspiration for the TTC in later years as an ode to the Blackburn cab. In addition to the taxi company, the Blackburns continued to build their wealth by purchasing properties all over the city, notably in St. John’s Ward. Lucie added money manager to her role as she managed their investment properties, even becoming a mortgage broker in her later years.

Learn more about the Blackburns, their escape from slavery, and how they came to Toronto.

Thornton and Lucie Blackburn’s gravestone, Toronto Necropolis Cemetery, January 19, 2024.

The Blackburn Plot

An interesting tidbit of the Toronto Necropolis was the fact that it’s rare to see women’s names on gravestones from the 19th to even the 20th century.

Although we don’t know the exact reason, Lucie’s influence in erecting the final resting place for her husband and their family is subtle but apparent. When Thornton died in 1890, it was Lucie who erected the towering red granite obelisk as a tribute to her beloved. She was also the one who wrote his obituary featured on his grave.

Lucie passed away five years later on February 6, 1895 and was buried by her husband in April 1895. The final resting place of the Blackburns also gives us a glimpse into Black community-building between freedom seekers arriving in Toronto through the Underground Railroad and established Black families. The Blackburns are not the only ones buried in their plot at the Necropolis, another prominent Black family rests beside them: the Jacksons.

In Memory of Thornton Blackburn,

Epitaph of Thornton Blackburn, written by Lucie Blackburn

Died Feb. 26, 1890, Aged 76 Years

A Native of Kentucky, USA

Blessed are the Dead which Die in the Lord

Found on Thornton Blackburn’s tombstone

Toronto Necropolis, May 30, 2019. Image by Kristen McLaughlin.

The Jackson Family

The Fugitive Slave Act in 1850 in the United States led to an increase of Black people escaping slavery or incarceration arriving in Toronto.

The story of the Jackson family begins in Delaware with Ann Maria Jackson and her husband John Jackson, who together had nine children. Although John was a free Black man who worked as a blacksmith, Ann Maria and her children were enslaved but they were all allowed to live together as a family. Two of their sons, James and Richard, were sold to another enslaver which was devastating to the family. John Jackson was profoundly affected by the separation of the family: he later passed away due to grief at a local almshouse, known today as an asylum or mental health institution. When Ann Maria learned that her owner had plans to sell her remaining seven children, she took the risk and fled with her children through the Underground Railroad, arriving in Canada in November 1858.

The Jacksons arrived in St Catharines before making their way to Toronto, arriving at the home of Thornton and Lucie Blackburn. The Jacksons stayed at the Blackburns before relocating to St. John’s Ward and the families remained life-long friends. In addition to finding community with the Blackburns, Toronto would be the place where the Jacksons would be reunited with James and Richard, who both also escaped through the Underground Railroad and ended up in Toronto at different times.

The Jacksons enjoyed a successful life in Toronto but it didn’t come without its struggle or heartbreak. Ann Maria and her son Richard are buried in the Blackburn plot at the Toronto Necropolis, speaking to the friendship between the Jacksons and Blackburns.

Albert Jackson and his family, Toronto, 1980. Courtesy of Lawrence Jackson.

It almost broke my heart. He came and took my children away as soon as they were big enough to hand me a drink of water.

Ann Maria to William Still

Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Society

Albert Jackson

As the first African Canadian letter carrier in Toronto, Albert Jackson carried on the legacy of his family.

Buried a few yards away from his mother and brother in the Necropolis is Albert Jackson, the youngest of Ann Maria’s nine children. Albert grew up in St. John’s Ward where his family lived in rented rooms there and were active members of the growing Black community in Toronto, many of whom resided in the Ward.

Once Albert finished school, he applied for a job at Canada Post as a letter carrier. At the time, Black people coming to the city were mainly working menial jobs such as labourers, waiters and other service jobs. Simultaneously, there was a growing number of established business owners like the Blackburns who, through their wealth, were able to create jobs for other Black newcomers seeking employment. In those days, a postman was considered one of the highest positions a person could have, in addition to the fact that it was a government job. It was even more scandalous for a Black person to apply for a position like a letter carrier. However on May 12, 1882, Albert was hired as a letter carrier for Canada Post, being the first African Canadian to hold that position.

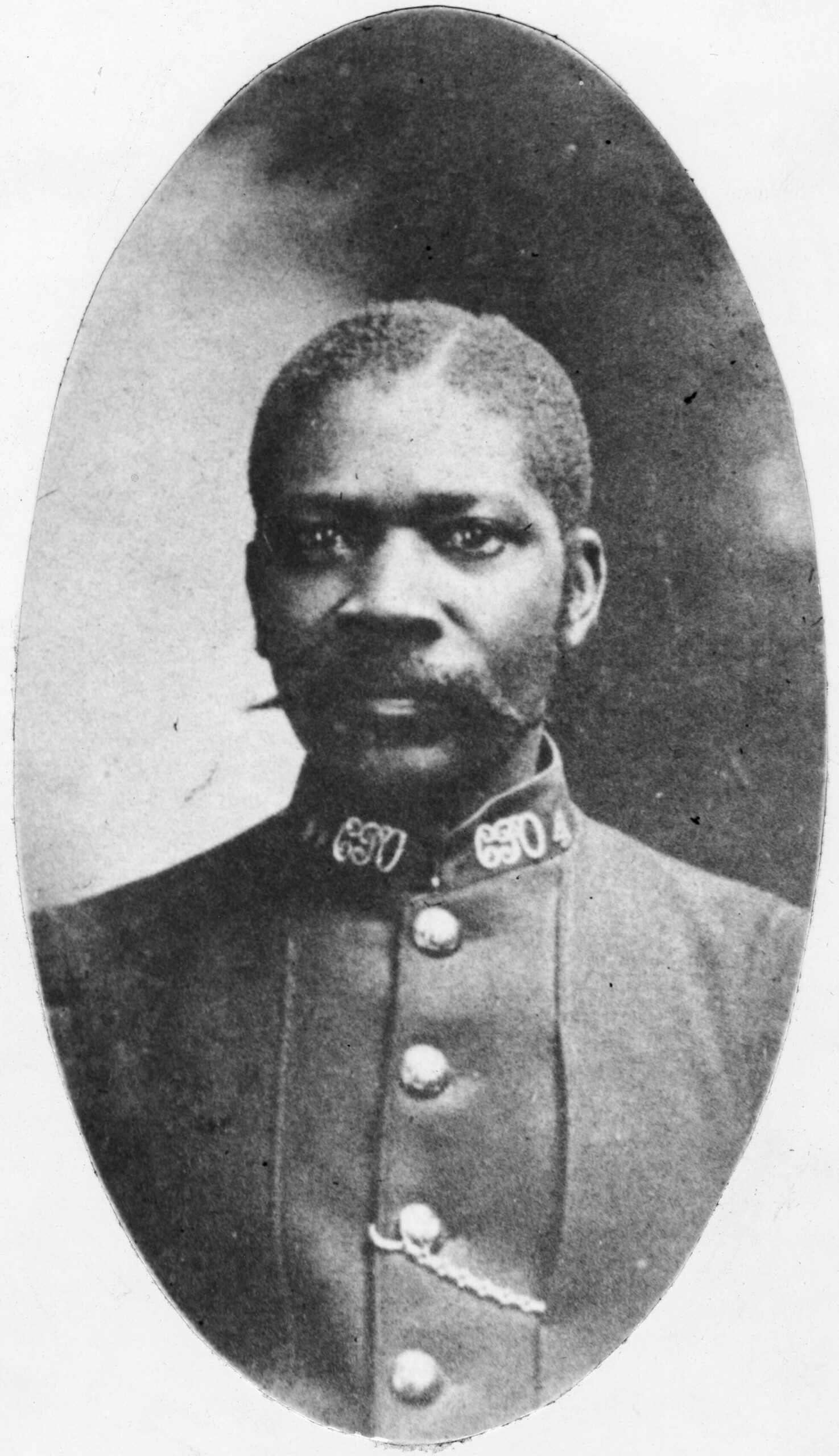

Albert Jackson in his letter carrier uniform, Toronto, Date Unknown.

The First Black Postman

Albert Jackson’s journey as the first Black mail carrier for Canada Post wasn’t easy.

When Albert showed up for his first day of work, his coworkers refused to show him the ropes, insulted by the fact that a Black man was able to be hired for an esteemed job like a letter carrier. Adding insult to injury, Albert’s supervisor decided to strip him of his duties and assigned him to be a janitor. The story of Albert Jackson became a national story in its day as members of the Black community protested against this injustice. Newspaper opinion pieces referred to Jackson as “The Objectionable African” with the public debating. The Black community, in protest, created a committee to advocate to the government to reinstate Albert in his role.

On June 2, 1882, Albert was reinstated in his role as letter carrier and would hold that position for the next 36 years until his death in 1918. Like the Blackburns, Albert and his wife Henrietta bought investment properties in the Ward as well as in the Bloor and Bathurst area on Brunswick Avenue and Harbord Street. Henrietta died in 1958 at the age of 99 and is also buried beside her husband at the Necropolis. Buried only a few steps away from their tombstone is their oldest son Alfred who passed away in 1901 at the age of 17.

The Jackson legacy continues: Albert was honoured in 2019 by Canada Post with a commemorative stamp. The Albert Jackson Postal Processing Facility opened in September 2023 in Scarborough making history as the first zero-carbon facility in the city.

I think often about the cushy life I lead and how they [Albert & Henrietta Jackson] just paved the way for all of my family so that we could have what we have today.

Shawne Jackson-Troiano, great-granddaughter of Albert Jackson

CBC, July 2017

Gravestone of Albert C. Jackson and Henrietta E. Jackson, Toronto Necropolis Cemetery, September 19, 2023. Image by Oscar Akamine.

Honouring Black Legacy Beyond the Grave

The Necropolis is not just a cemetery, it’s a community that we continue to learn lessons from even in the afterlife.

The Necropolis holds many more stories of people who lived eccentric, unassuming yet extraordinary lives. There are many others buried in the cemetery who were likely connected to the Blackburns and the Jacksons. Toronto’s first Black acting mayor William Peyton Hubbard and his family, the Abbott Family including Toronto’s first Black City Councillor Wilson Ruffin Abbott and his son Dr. Anderson Ruffin Abbott, one of the first African Canadians to obtain a medical license. There are more stories to be told, more connections to make.

The Necropolis is a reflection of the interconnected ecosystem that the Black Community was able to create that has transcended both life and death as we reflect on how it comes to life today.

Sponsor

References and Further Resources

More than half of Canada’s Black population calls Ontario home. Statistics Canada

Karolyn Smardz Frost, I’ve Got a Home in Glory Land: A Lost Tale of the Underground Railroad (2007)

Albert Jackson. The Canadian Encyclopaedia.

Toronto Then and Now: # 4 ~ Saint John’s Ward and Kensington Market, Then and Now

Detroit’s First Race Riot & Toronto’s First Cab Company – Black Mail Blog (blackmail4u.com)