Unveiling Heroes: Blackburns

The Blackburns

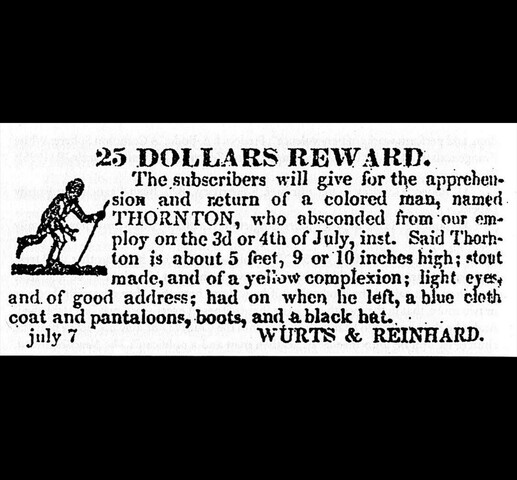

Fugitive Slave Notice for Thornton Blackburn, Louisville Public Advertiser, July 7, 1831.

The Skillman Branch of the Detroit Public Library, 2007. Image: Mikerussell, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

John Scadding’s cabin with Thornton Blackburn’s taxicab parked in front, 1895. Courtesy of York Pioneer and Historical Society Archives.

Born in enslavement

Thornton Blackburn was born into enslavement in Kentucky. Separated from his mother at a young age, Blackburn was forced to work as a child, including driving carriages and working as a porter. As a teenager, Thornton met “Ruthie” (later known as Lucie), an enslaved, Caribbean-born woman who was working as a nursemaid.

Thornton and Ruthie gained permission from their owners to marry in 1831; however, even after they were married, as enslaved persons, they were subject to the whims of their owners. Ruthie was sold to slave owners based in New Orleans, where enslaved women were often forced to become sex workers. Fearing the worst, the Blackburns took action. Carrying forged papers asserting their freedom, Thornton and Ruthie made their way north.

A Detroit escape

Thornton and Ruthie navigated the 300-kilometer journey from Kentucky to Michigan largely alone. Once they arrived in Detroit, the Blackburns were welcomed into a small and supportive community of free African Americans. But danger was not past: Thornton and Ruthie were declared fugitive slaves, resulting in their capture, imprisonment, and trial in 1833.

The Blackburns were sentenced to return to bondage in the southern United States. But supporters from Detroit’s Black community rallied to their cause. On June 16,1833, Ruthie swapped clothing with a prison visitor and was secreted across the border into Canada. The next day, a crowd overwhelmed Thornton’s captors on the docks of the Detroit River, allowing him to make his way to Canada. Later known as the Blackburn Riots of 1833, these events sparked one of the first race riots in Detroit’s history. It also established a strong community of skilled, free Black people who made the city an important stop along the Underground Railroad.

A new life in Toronto

Although slavery was illegal in Canada by the 1830s, the Blackburns were not yet out of danger. The governor of Michigan demanded their return. In a groundbreaking case, Canadian courts declared that the Blackburns could not be forced to return to the United States. The case became foundational to Canada’s extradition laws; it also established Canada as a safe end point to the Underground Railroad. Shortly after the case was decided, Ruthie changed her name to Lucie to celebrate her liberation.

Settling in Toronto, the Blackburns became entrepreneurs. In 1837, Thornton and Lucie established Toronto’s first taxicab service, called The City, which was a horse-drawn cab with one horse and a carriage painted yellow with red trim (the future colour scheme of the TTC). The Blackburns were also deeply involved in their new community, donating to civic building projects and helping freedom seekers arriving in Canada. They frequently rented out several of their properties to newcomers to Toronto.

The cause for freedom

In 1850, the U.S. government passed the Fugitive Slave Act: the controversial law imposed stiff penalties for anyone escaping enslavement or helping others to do so. After the passage of the law, increased numbers of freedom seekers moved north to Canada to avoid the long reach of the Act. Over 15,000 African Americans came to Toronto between 1850 and 1860. Toronto became a hub for abolitionist activities during this time, including hosting the North American Convention of Coloured Freemen, which was held at Toronto’s St. Lawrence Hall in September 1851.

Alongside abolitionists from Canada and the U.S., Thornton and Lucie Blackburn participated in the Convention as delegates, discussing strategies for assisting fugitive slaves and how to bring about the end of slavery. The Blackburns remained active in the abolitionist community for years following, only retiring from public life in the 1860s. Thornton and Lucie died in the 1890s and were buried alongside their family in the Toronto Necropolis.