Japanese Internment: Growing Community in Postwar Toronto

Japanese Canadians suffered race-based internment policies during World War II and were displaced to eastern Canada. The resilience of Japanese-Canadians in postwar Toronto has resulted in a community rooted in advocacy, collective memory, and cultural preservation.

Contents

This story was researched and written by Emerging Historian Elizabeth Compa (2023) and made possible by the generous support of our Tours Program Presenting Sponsor, TD Bank Group through the TD Ready Commitment and Emerging Historian Champion Andrew and Sharon Himel and Family.

Last updated: May 15, 2024

We’d love to hear your feedback. Contact us.

Marginalization and Internment

Canada created internment policies based on race for both World War I and World War II.

During both world wars, the Canadian government enacted race-based policies that included sending thousands of people of specific ethnic origins to internment camps and programs, significantly affecting numerous Toronto communities as well as subsequent generations. This article explores how the legacy of these internment programs has affected, in particular, the Japanese-Canadian community and has shaped modern Toronto.

Internment is a very physical and extreme form of marginalization, like a semi-permanent banishment. On the basis of national origin and, in some cases, political affiliations, Canadian residents and citizens, including children, were stripped of property, detained, and sent to rural labour camps. This chapter of history vividly illustrates how communities in Canada, particularly immigrant communities and racialized minorities, have experienced various forms of marginalization throughout the country’s past and present.

This article uses the term “internment” in reference to the Canadian government’s specific policy choices. However, the term can be seen as overly clinical and insufficiently descriptive of the actual experience for those who lived it. For instance, in much of the Japanese-Canadian community, the events described here are considered more properly characterized as uprooting, dispossession, and expulsion.

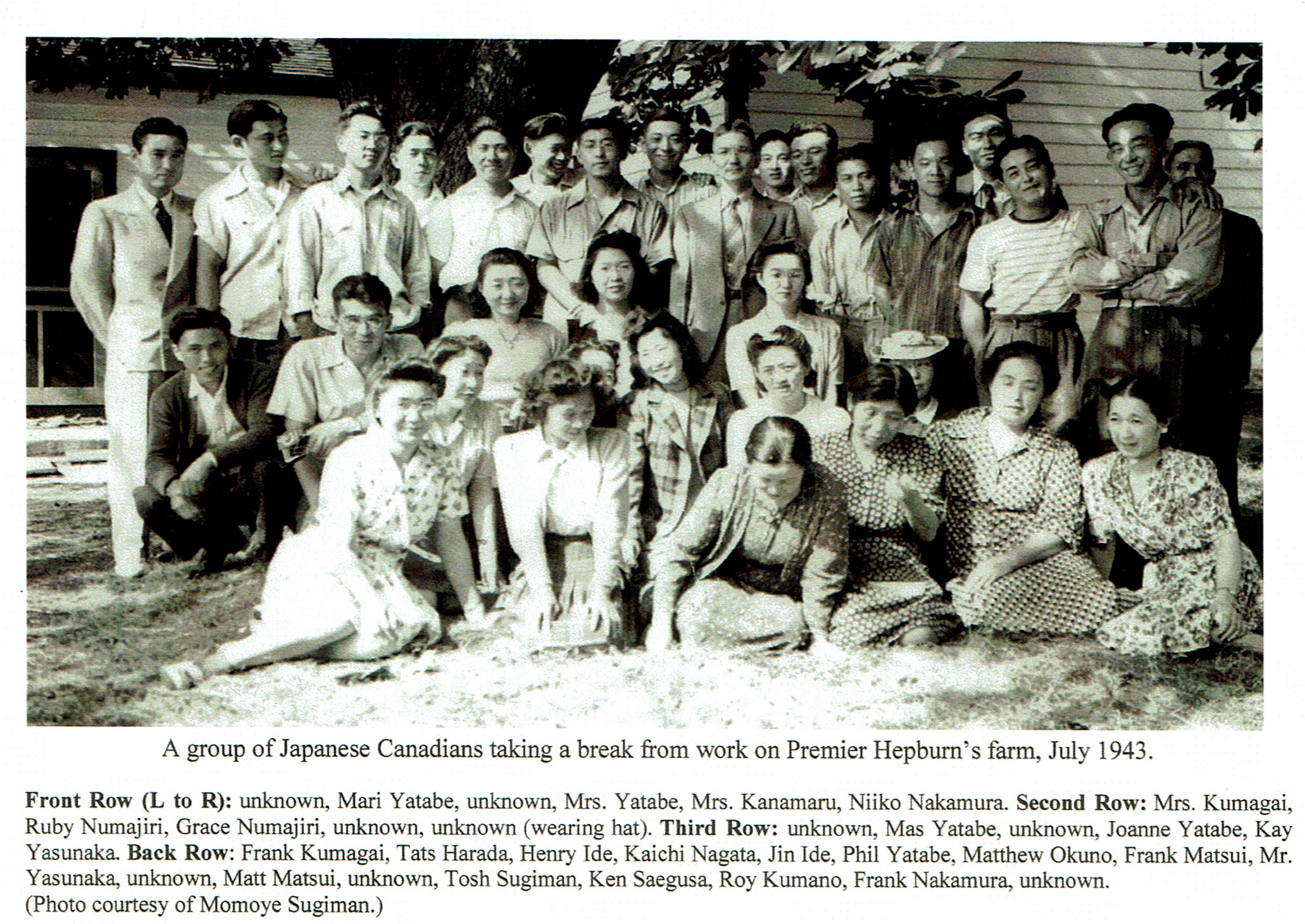

Japanese-Canadian labourers taking a break from work on Premier Hepburn’s farm, Elgin County, Ontario, July 1943. Tosh Sugiman located fifth from the back right. Image courtesy of Momoye Sugiman.

We could not move back to the [west] coast until 1st of April 1949…And so, what was there for us to go back [to], our house was sold, our businesses were gone. What was there? We had already established residence in Toronto since ’43. There was no incentive for us to go back.

Former internee Tom Matsui speaking to the Landscapes of Injustice Project, 2015.

Internment in Canada

Toronto played significant roles in Canada’s internment policies during both World Wars, but in different ways.

Toronto had important but distinct roles in Canada’s internment policies during both World War I (with relevant policies in effect from 1914 to 1920) and World War II (with relevant policies in effect from 1942 to 1949).

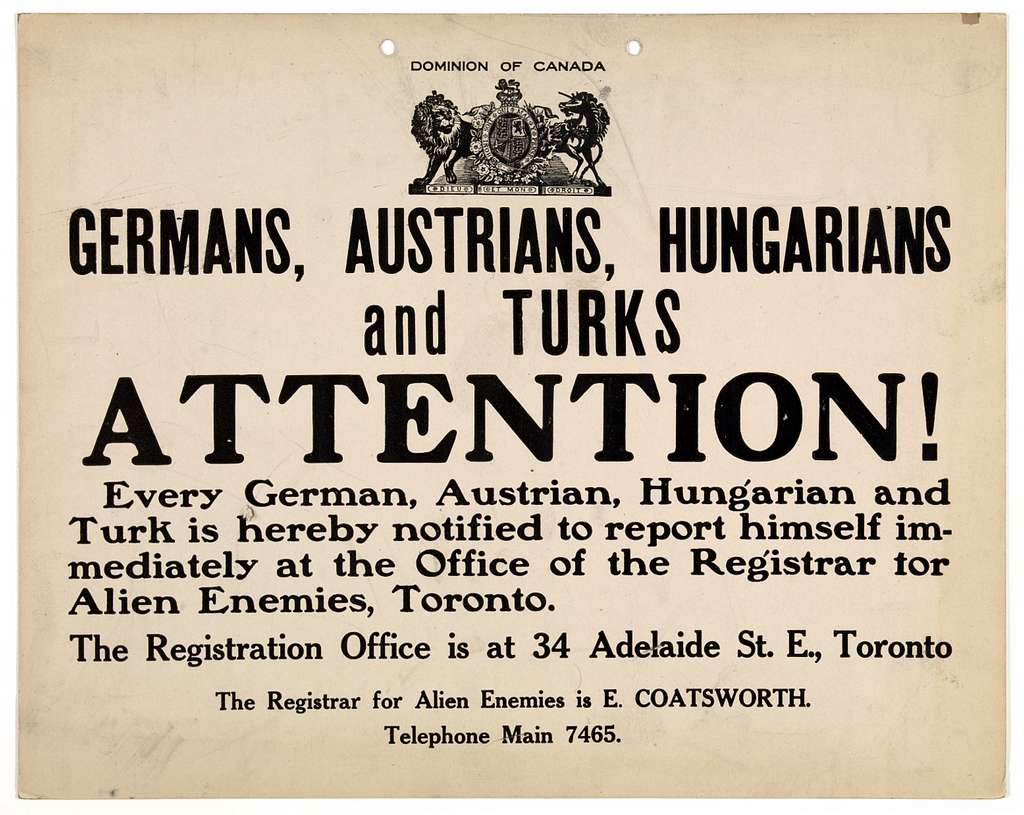

In both instances, the policy of internment targeted so-called “enemy aliens,” people perceived as posing a security threat because of their ethnic origin. In World War I, this comprised people of Austro-Hungarian, German, Turkish, and Bulgarian origin. In World War II, those most severely impacted were Japanese Canadians. People of German and Italian origin were also affected, and even some Jewish refugees who arrived in Canada during the war were sent to internment camps.

Notably, not all “enemy aliens” were interned. Some faced other methods of marginalization, such as being forced to report to authorities regularly or having their freedom of movement restricted. While various ethnic communities were subjected to race-based policies under the guise of wartime security, the numbers, duration, and degree of disruption varied. For Japanese Canadians in particular, the consequences of internment were often life-altering.

Toronto Registrar’s office poster instructing people of certain national origins to register as “Alien Enemies”, ca. 1914. Courtesy of the Archives of Ontario.

We had to go East of the Rockies, it was a mandate by the government… Vancouver was not an option. And [it was] your only time to get out of the camp, so go East…. So, Toronto became home, and once it became home, it became permanently home.

Former internee Peter Kurita speaking to the Landscapes of Injustice Project, 2015.

Toronto’s Role in WWI Internment

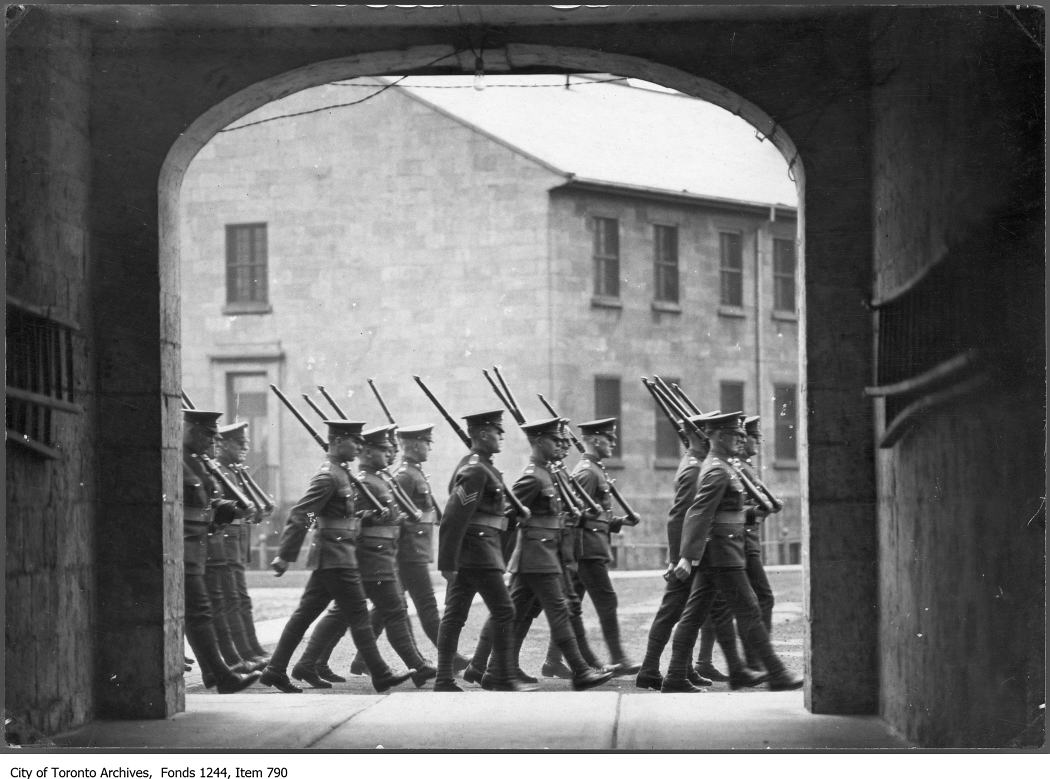

The Stanley Barracks, located at Fort York, was a Toronto internment site during World War I.

The Stanley Barracks, located on what is today the Fort York National Historic Site, began housing prisoners of war in the fall of 1914, and was an official receiving station – where new internees were administratively processed – from December 1914 to October 1916.

As early as October 1914, the Toronto Daily Star reported that people arrested in Ontario under the War Measures Act, which gave the government increased power and control, were being “sent to Toronto to be looked after.” The newspaper noted that the barracks had been modified to facilitate holding people there, “A large open space is being fenced off at the Barracks with a double barrier around it to serve as a detention camp for the Austrian and German prisoners.”

As the infrastructure of internment grew, the barracks transitioned to having a more administrative role, often sending detainees to rural labour camps throughout Canada to work on large-scale infrastructure projects. Conditions at such camps were often poor, and infectious diseases were common.

Troops perform a drill at Stanley Barracks, 1918. Courtesy of the City of Toronto Archives.

The Legacy of WWI Internment in Toronto

Over 8,500 men were interned in Canada during World War I.

Over the course of World War I, Canada interned 8,579 men in 24 camps and receiving stations nationwide. According to government records, over sixty percent of these men were Austro-Hungarian (mostly Ukrainian). Other nationalities included men from Germany, Turkey, and Bulgaria. More than half were civilians rather than prisoners of war. Official records also show that 81 women and 156 children were voluntarily interned, likely as relatives of the interned men.

In some cases, unhoused people, conscientious objectors, and some members of banned cultural and political associations such as the Industrial Workers of the World were interned, especially after Russia’s 1917 Bolshevik Revolution as domestic concerns about revolutionary politics increased.

The War Measures Act remained in effect until 1920. Fort York became a national historic site in 1923, just a few years later. At the time, the city was still reeling from the immense impact of the war as a whole, which saw roughly 2% of the city’s population of men perish.

Today, the site welcomes thousands of visitors annually to learn about the Battle of 1812 and other military histories in Toronto – but visitors rarely hear or read about the site’s role in processing Canadian residents for internment in labour camps. However, a $10 million community settlement fund to support education and commemoration of internment during World War I was established in 2008 and signed at Fort York.

View of Fort York lawn, looking east, May 26, 1980. Courtesy of the City of Toronto Archives.

I felt sorry for my brother and my mother who worked so hard to support the family and they lost everything. Whereas, the younger ones like myself and my sister, we came to Toronto and finished off our schooling. So we didn’t feel the loss as much, because we didn’t have anything when we were younger. We got a fresh start.

Former internee Tom Matsui speaking to the Landscapes of Injustice Project, 2015.

Japanese-Canadian Internment in WWII

The 1941 attack on Pearl Harbour triggered another government policy of internment and displacement.

Toronto played a decidedly different role when Canada again turned to a policy of internment during World War II. In total during the war, some 24,000 people were sent to 40 internment camps across Canada, including people of German and Italian origin, refugees of Jewish origin, and political prisoners with left- and right-wing affiliations. But the Canadians whose lives were most upended by internment in World War II were the tens of thousands of Japanese Canadians living on the West Coast.

Even before World War II, Japanese Canadians were limited to second-class citizenship: denied the right to vote and subject to prejudice and exclusion as workers, even for those born in Canada. The racism underlying that status was further inflamed with the outbreak of war.

When Japan attacked Pearl Harbour in December 1941, more than 20,000 Japanese Canadians living in and around Vancouver were forced from their homes, often with only 24 hours’ notice. Their property was seized and often sold. Many Japanese Canadians were sent to hastily realized camps in abandoned mining towns in inland British Columbia (mostly women and children), road labour camps (mostly able-bodied men), or prison camps spread across the country. Although many were sent to camps in British Columbia, others were sent as far away as southern Ontario, often to sugar beet and tobacco farms. A group of about 25 people laboured at the Elgin County farm of Ontario Premier Mitchell Hepburn.

In August 1944, Canadian authorities announced another race-based policy that would alter the country’s – and Toronto’s – demographic composition: that Japanese Canadians in British Columbia must move east of the Rocky Mountains following the end of the war or be expatriated to Japan. This policy lasted until 1949, when Japanese Canadians were granted full freedom of movement in the so-called ‘protected zone’ along the British Columbia coast, but by then, many had built lives elsewhere.

Cover art for the pamphlet They Made Democracy Work: The Story of the Cooperative Committee on Japanese Canadians. Original photograph of a full colour painting, “Evacuation,” by Fred Kondo. Courtesy of the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre.

[W]hen we first came to Toronto, and I re-met my friends that I had before, we were very thankful that the Metropolitan United Church made themselves very available to the Japanese community. We… were all in a group that loved to play tennis and badminton. [The] Church there made themselves very available to use their gym for recreational purposes, and we really appreciated that.

Former internee Jean Ikeda-Douglas speaking to the Landscapes of Injustice Project, 2015.

Encountering Toronto: Postwar Arrival of Japanese Canadians

Grassroots groups were instrumental in finding housing for displaced Japanese Canadians.

Prior to World War II, the Japanese community in Toronto was very small – a “tiny coterie” of as few as 20-30 people, according to Roger Obata, who arrived in Toronto from Vancouver in 1937. From 1942 to 1945, the City of Toronto barred Japanese Canadians from moving to Toronto without sponsorship, meaning a person or organization who would take responsibility to provide housing and employment for the new arrivals. Despite these impediments, Toronto became home to thousands of Japanese Canadians.

Civic groups in the city began organizing to facilitate the settlement of Japanese Canadians in the region. The Cooperative Committee on Japanese Canadian Arrivals in Toronto (CCJC), a women- and Protestant Church-led organization with political ties to the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation party, was formed to assist in the effort to find housing, identify job paths, and organize recreational activities.

The CCJC held its first meeting at the YWCA on McGill Street on June 8, 1943. The most immediate task was the resettlement of tens of thousands of Japanese Canadians still held in camps: where they should go, and how to “avoid segregation” as they settled east of the Rockies.

The group faced a challenging goal: finding sufficient housing for the new arrivals; finding employment opportunities when the city’s official policy was still exclusion; and even finding recreational opportunities for young people when racialized bigotry was common throughout the City.

YWCA Building, 21 McGill Street, June 23, 1929. Image courtesy of the City of Toronto Archives.

It soon became apparent to those of us who had established ourselves in Toronto years earlier that these new arrivals needed some organized assistance to get settled… but this had to be done inconspicuously through silent networking. We could not let Torontonians know that we were here in any significant numbers. Remaining invisible was of utmost importance.

Roger Obata, Japanese Canadian Redress: The Toronto Story (2000)

Building Power and Community in Toronto

Anti-Japanese discrimination made it very difficult for Japanese-Canadians to secure employment and housing in postwar Toronto.

Roger Obata was among the small number of Japanese Canadians living in Toronto during the 1930s. The discrimination that excluded Japanese Canadians in Toronto from professional jobs and narrowed housing prospects motivated Obata and others to found the Japanese Canadian Committee for Democracy (JCCD) in 1943. The JCCD worked alongside the CCJC to help meet the needs of Japanese Canadians arriving in Toronto.

The CCJC- and JCCD-led assistance with housing, employment, and recreation were necessary to overcoming the discrimination many Japanese people experienced on arriving in Toronto — but they were not sufficient. Another religious and ethnic group that played an important role in this chapter was Toronto’s Jewish community, whose members had felt firsthand the prejudice of Toronto’s broader, mostly Anglo-Canadian, population; were acutely aware of the unprecedented horrors being inflicted on Jewish people in Europe at the time; and held a centuries-long cultural tradition of struggle against oppression.

“Our shared experience as victims of racism somehow created a bond between the Japanese and Jewish communities in Toronto,” Roger Obata recalled. “[M]any members of our community, male and female, were employed in Jewish owned garment factories along Spadina Avenue. Having experienced persecution themselves, the Jews in Toronto showed their support and solidarity in the most practical manner by employing us when very few others would give us any jobs whatsoever.”

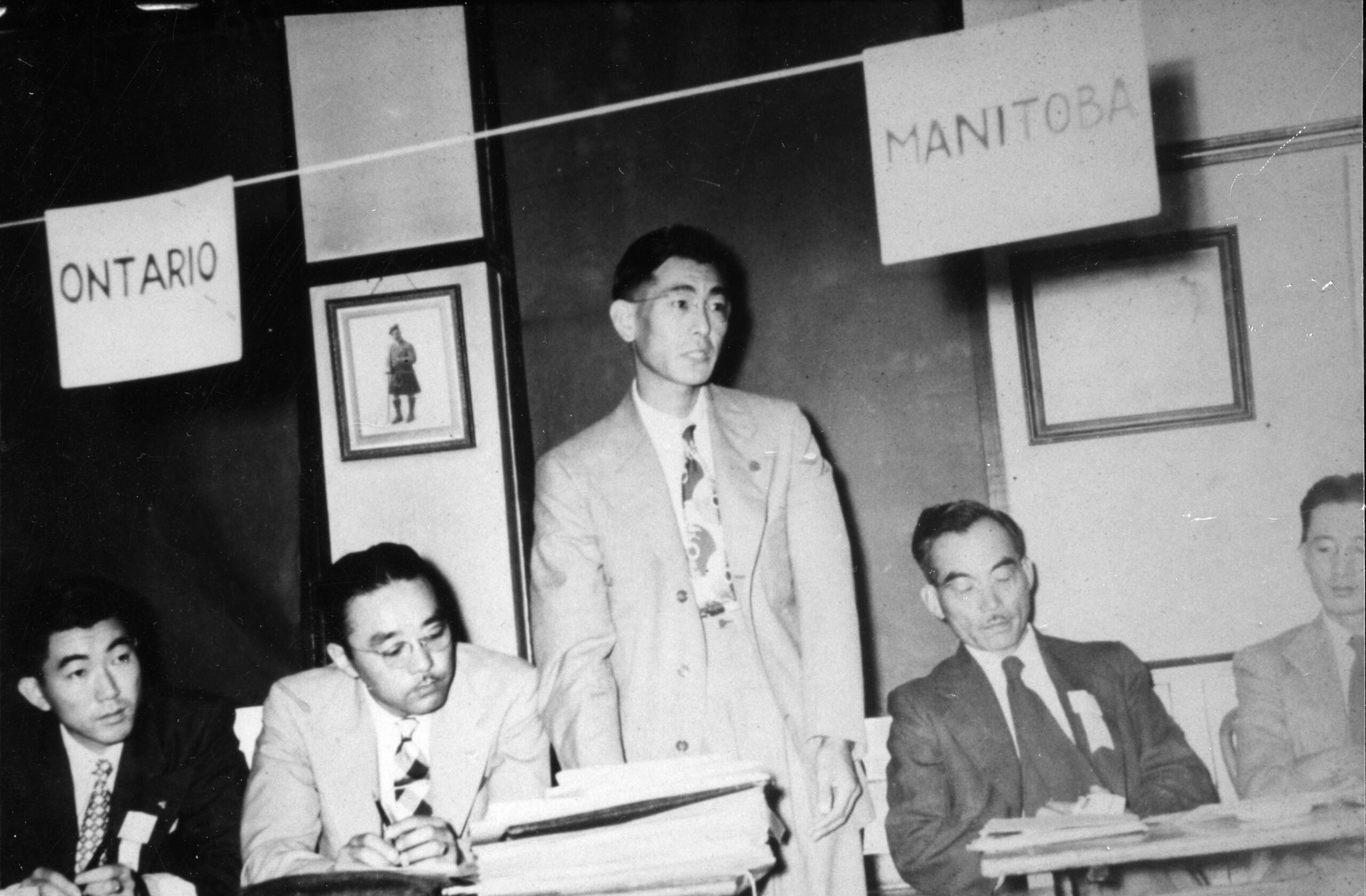

Over time, as the immediate needs of people settling in Toronto became less acute, JCCD leaders founded a successor organization in 1947 – the National Japanese Canadian Citizens Association (NJCCA). It became an essential organizing body for the Japanese community both in the city and across the country. Roger Obata was its first president.

The NJCCA and CCJC would work in coalition with other groups, including labour unions and religious organizations across faiths, as they shifted from the early focus on direct assistance to broader and more sustained strategic organizing campaigns, especially around efforts to prevent forced deportations and stop the passage of discriminatory laws.

The first convention of the National Japanese Canadian Citizens’ Association, Toronto, 1947. From left to right, Edward Ide, Roger Obata, George Tanaka, T. Umezuki and Harold Hirose. Courtesy of the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre.

I knew nothing about the internment growing up in the 1950s in the east end of Toronto here…. I knew we were Japanese, I mean my mother made sure — ‘You are Japanese, don’t forget that.‘

Terry Watada, oral history with the Landscapes of Injustice Project, 2015.

Growing up Japanese-Canadian in Postwar Toronto

New generations continue to learn about their family’s resilience and the legacy of internment.

As Japanese Canadians built their lives in Toronto over the postwar decades, their families grew and new generations came of age. Members of the Baby Boom generation, born in Toronto after the war’s end, forged a new path of Japanese-Canadian identity that was informed by the upheavals their parents and older siblings experienced – even in instances where those experiences went undiscussed for years.

Terry Watada was born in Toronto in 1951 and grew up in Leslieville. He did not learn about his parents’ and older brother’s internment until he reached adulthood. “[I] really didn’t question anything that happened in my past, I just accepted everything as it was. But then I went to university,” he said.

He joined a group of Japanese Canadians that gathered regularly “to discuss themes of identity, racism, all kinds of topics.” At a conference, he saw photos of the internment camps for the first time. “And it was quite something, it just — yeah, surprised me. I could use the term ‘blew my mind,’” he recalled. “So then I had to ask my parents, right? Did this really happen? And of course my mother just said … ‘You don’t need to know this stuff. Why do you want to know that stuff for?’”

Mr. Watada’s drive to learn more of his family’s story intensified when he decided to pursue songwriting. “And first rule is, what do you write about? You write about yourself. And I realized that I didn’t know anything – and there’s this internment thing, and so after I got the first rebuke from my mother [I said,] ‘Well, you know, what’s so stupid about it? I want to know.’ Finally I did get through.”

Momoye Sugiman was born in Toronto and grew up in the Bloor West neighbourhood. Her father, Tosh Sugiman, was one of the 25 labourers who was sent to Premier Hepburn’s farm before settling in Toronto.

Reflecting on the construction of Japanese Canadian identity in Toronto, she recalls aspects of her childhood – institutions and traditions that the older generations had built and maintained – that helped foster a sense of community, safety, and cultural preservation. The Toronto Buddhist Church on Bathurst Street and the Japanese Anglican Church both played a significant role, as did food. New Year’s Day was especially important, when families would pay visits to each other to enjoy once-a-year delicacies.

Ms. Sugiman recalls how she came to embrace her Japanese Canadian identity in a more political way as a teenager – including choosing to use her Japanese middle name rather than her Anglo given name – in part thanks to an Anglo-Canadian history teacher who encouraged her to explore that history. “And then I started to feel angry. He really politicized me,” she recalls. “My mother said, ‘Why do you want to dredge all that up?’”

Garden Opening Ceremony at the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre, founded in 1963. Courtesy of the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre.

We used to have a simple Japanese meal once per week, but it was only on New Year’s Day that my mother would prepare an enormous feast: beautifully arranged sushi, octopus, and other expensive Japanese dishes. She would put aside funds for months to afford the ingredients. It was only on New Year’s Day that we had several visitors dropping by from noon until the evening.

Momoye Sugiman

Remembering and Redress

The Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre works to preserve and empower identity, culture, and history.

The Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre (JCCC), founded in 1963 in Toronto, has become a fulcrum of exploring identity and history. The JCCC and other projects, including the Landscapes of Injustice project whose interviews are cited in this article, took up the work of documenting the recollections of people who were interned as well as their children, archiving historical materials, and sharing this multiplicity of voices in order to preserve the stories for future generations.

In the decades following World War II, Japanese Torontonians continued to self-organize and -advocate. In the 1980s, the NJCCA, now known as the National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC), led a successful push for governmental redress, which called for not only compensation for the period of internment but also protections against a policy of internment ever being used again to perpetrate racial discrimination in Canada. The redress agreement signed in 1988 included individual compensation, a community fund, pardons for those wrongfully imprisoned, citizenship for those wrongfully expatriated, and a formal apology from Prime Minister Brian Mulroney.

Momoye Sugiman’s exploration of identity has become a lifelong endeavour. She edited the 2000 book Japanese Canadian Redress: The Toronto Story and conducted several of the interviews from 2015 that are part of the Landscapes of Injustice oral history project, which her cousin Pam Sugiman led.

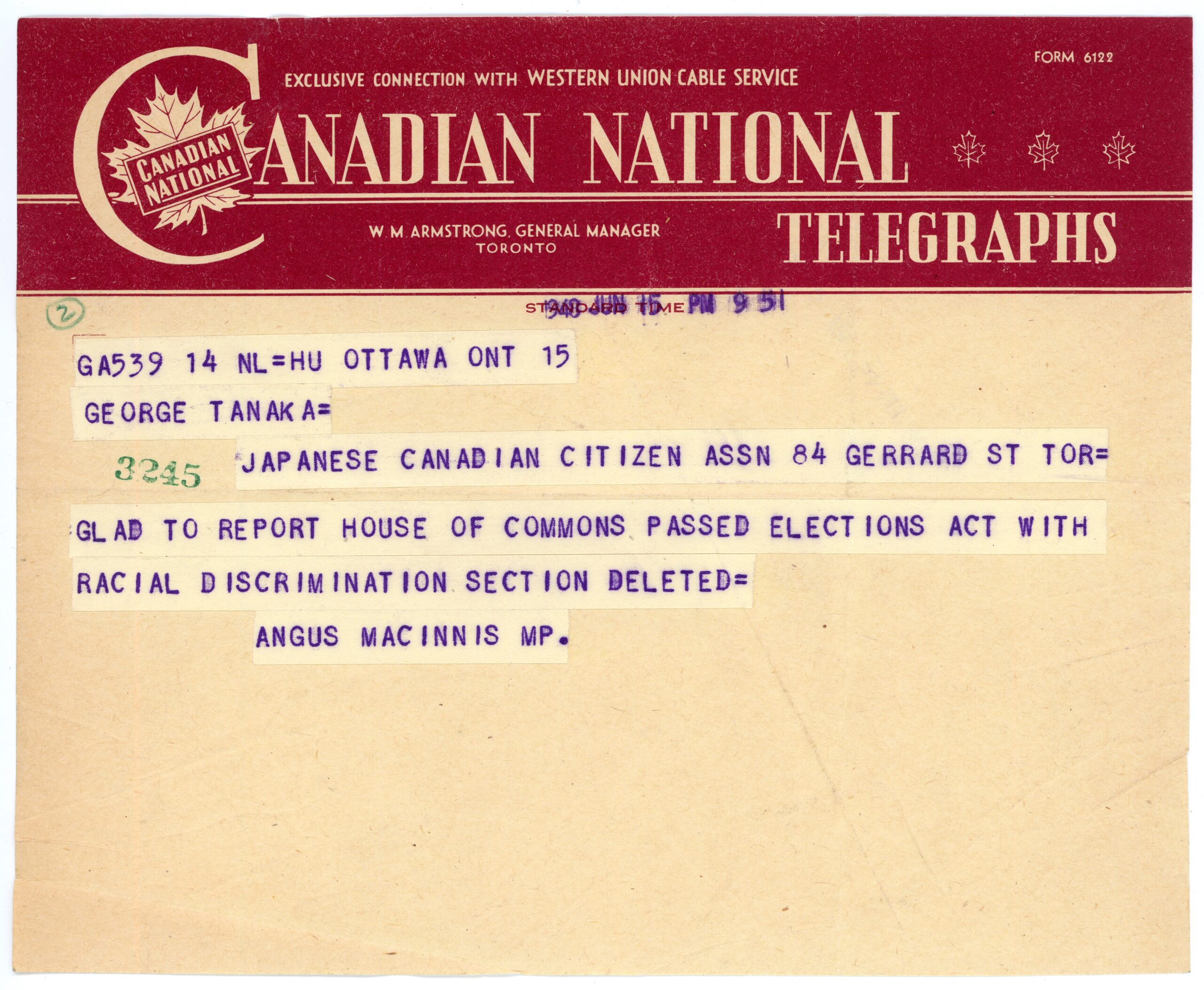

Telegram from MP Angus MacInnis to George Tanaka about Elections Act provision, June 15, 1948. Courtesy of the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre.

Here I was thinking I was Canadian the whole time and then I found out that Japanese Canadians didn’t get the vote until ’49. In fact they couldn’t even move around the country until ’49…. So I thought, jeez, am I Canadian? Am I accepted as a Canadian? If you can do this to my parents, you can do it to me.

Former internee Terry Watada speaking to the Landscapes of Injustice Project, 2015.

Remembering Internment in Toronto Today

Learning about Toronto’s history generates greater understanding of the city today.

Japanese Torontonians have made countless contributions in shaping the modern city. Among the most prominent examples in the built environment are three lauded projects by architect Raymond Moriyama, whose family was uprooted from Vancouver and initially settled in Hamilton after the war. He designed the original JCCC building at 123 Wynford Drive, the Ontario Science Centre in Don Mills, and the Goh Ohn Bell Shelter at Ontario Place. Notably, all three have been considered for demolition or removal in recent years, prompting groundswells of vocal community support for their preservation.

Toronto’s Japanese Canadian community continues to evolve, as new immigrants – or issei – arrive and new generations come of age. A significant number of Japanese Canadians in Toronto immigrated after the 1950s and have played an important role in the ongoing mission of community cohesion. For instance, a Japanese-language immersion daycare at the JCCC, where many staff are recent issei, offers children access to a linguistic knowledge base that their parents or grandparents in Toronto would likely not have had growing up.

Ideas about collective trauma and upheaval have grown more prominent in recent decades, and there has developed a consensus against the use of internment as a fundamental violation of people’s rights, not just in Canada but abroad. The events of the 20th century recede further into the past, but to better understand today’s Toronto, there is reason to revisit them.

“I think at the time that redress was settled people were keenly aware [of the story of internment]”, Terry Watada reflected in his 2015 interview. “But since then it’s waned. I think people know that it happened, and know the results of it, but it doesn’t matter to them anymore…. That’s a shame because it can happen again.”

These stories must be remembered, reflecting on their impact on people and place in Toronto. As Terry Watada said, “I think it’s up to Japanese Canadians, organizations like the National Association of Japanese Canadians to remind people of what happened and keep them mindful of the implications of the internment and make sure that it doesn’t happen again.”

Sponsor

References and Further Resources

Thank you to Momoye Sugiman, Theressa Takasaki, Vidhya Elango, and Samm Griffin for their insights, support, and assistance in the preparation of this digital story.

- Japanese Canadian Redress: The Toronto Story (2000)

- Landscapes of Injustice oral history project

- The Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre Archive & Collections

- Fort York National Historic Site