Black Feminist Activism in the 20th Century

During the late 20th century, Black feminists in Toronto often used an intersectional approach to challenge traditional feminism. Their activism involved protests tackling racism, police violence, sexism, homophobia and more issues facing Black women and women of colour.

Contents

This story was researched and written by Emerging Historian Alanna Brown (2023) under the Equity Heritage Initiative made possible by the generous support of our Tours Program Presenting Sponsor, TD Bank Group through the TD Ready Commitment.

Last updated: March 6, 2024

We’d love to hear your feedback. Contact us.

Sisters in the Struggle film still, Dionne Brand and Ginny Stikeman, 1991. Courtesy of NFB.

Defining Intersectionality

Intersectionality is crucial in discussing the history of Black feminist activism in Toronto.

Beginning in the late 20th century, intersectionality has guided feminists on how to tackle intersecting forms of discrimination. The term ‘intersectionality’ was coined in 1989 by Kimberlé Crenshaw, an African American scholar and activist. She created this term to help describe how gender and race intersect and create barriers for Black women. In this, Crenshaw explained that when a Black woman experiences discrimination, it is not due to racism or sexism, but rather a combination of both.

Intersectionality can be seen throughout recent events and movements in Toronto’s history, notably in 1989 with International Women’s Day (IWD) events held throughout Toronto. Together, several organizations and movements, including the Black Women’s Collective, the Toronto Chapter of The Congress of Black Women and the Coalition of Visible Minority Women requested that the theme of IWD be an intersectional one, notably ‘women and poverty’.

Since then, intersectional feminism has evolved to include other grounds of discrimination. Intersectionality tackles discrimination on the grounds of race, sex, gender, sexuality, class, age, disability, religion and more. The expansion of intersectionality was crucial to feminism as it sought to include more marginalized identities.

As we look back through history of the 20th century, we see that Black, feminist-led organizations used intersectionality to bring the voices of Black women into mainstream feminism. Archival spaces in Toronto have documented this activism, allowing us to explore Toronto-based activism, such as by the Toronto Chapter of the Congress of Black Women and the Black Women’s Collective.

Intersectionality draws attention to invisibilities that exist in feminism, in anti-racism, in class politics, so obviously it takes a lot of work to consistently challenge ourselves to be attentive to aspects of power that we don’t ourselves experience.

Kimberlé Crenshaw, April 2014

Congress of Black Women: Toronto Chapter

The Congress of Black Women: Toronto Chapter used a cactus symbol in their logo to symbolize the strength and resilience of Black women – “no matter how arid the soil, the Cactus survives, multiplies and bears fruit.

In 1973, Kay Livingstone chaired the first National Congress of Black Women conference in Toronto with support from The Canadian Negro Women’s Association (CANEWA). At this conference, concerns relating to Black women such as education and parenting were discussed. The decision was made to create a national organization for Black women and the Congress of Black Women (CBWC) was born.

The CBWC included Black women from across the diaspora, including those from the Caribbean, South and North America and Africa. The organization included Black women from all working classes and ages, persons with disabilities, as well as those from the LGBTQ+ community. The organization sought to connect with other women and feminist organizations.

The CBWC ran as a voluntary and nonprofit organization. The Toronto chapter provided various services such as racism and sexism advocacy, workshops and conferences, project development, as well as employment and immigration. The Honourable Dr. Jean Augustine founded the Toronto chapter in 1983 and became the national president of the organization in 1987.

The goal of the organization was to bring together and support Black women from all areas of the Black community and help them to deal with sexism, racism and any other discriminatory practices. The organization also provided workshops to educate the public on issues relating to Black women and feminism.

The Congress of Black Women continues to run various chapters across Canada and provides an extensive amount of resources for Black women. The Toronto chapter ran from 1983 to 2002, then ran semi-actively until 2012.

Congress of Black Women of Canada Toronto Chapter Information Brochures. Date unknown. Courtesy of The Congress of Black Women Ontario & Rise Up! Feminist Digital Archive.

Black Women’s Collective

The Black Women’s Collective (1986 – 1989) used an intersectional approach in their activism to ensure that all Black women felt welcome.

The Black Women’s Collective (BWC) was an organization that emphasized intersectionality in their fight against discrimination such as homophobia, sexism, racism and classism. The collective voiced their opinion on racial and feminist issues within Toronto such as protesting police violence, as well as representation in Toronto’s International Women’s Day organizing.

The BWC worked with the Congress of Black Women Toronto Chapter and the Coalition of Visible Minority Women to propose a change – that was successful – to the theme for Toronto’s 1989 International Women’s Day celebrations to “women and poverty”. The goal of this change was to show how poverty affects women through the intersection of race and class.

The objectives of the Toronto Black Women’s Collective included organizing (events, protests and campaigns), encouraging Black women to become more involved in the struggle for liberation of themselves and marginalized peoples and to strive towards an equal society that would benefit everyone.

The BWC created “Ba-thari Day”, an International Black Women’s Day that took place on May 24, 1987. The day included several workshops on various topics such as racism and sexism in the workplace and black heritage along with performances by Lillian Allen, Audri Zhina Mandiela, Faith Nolan and Audrey Rose.

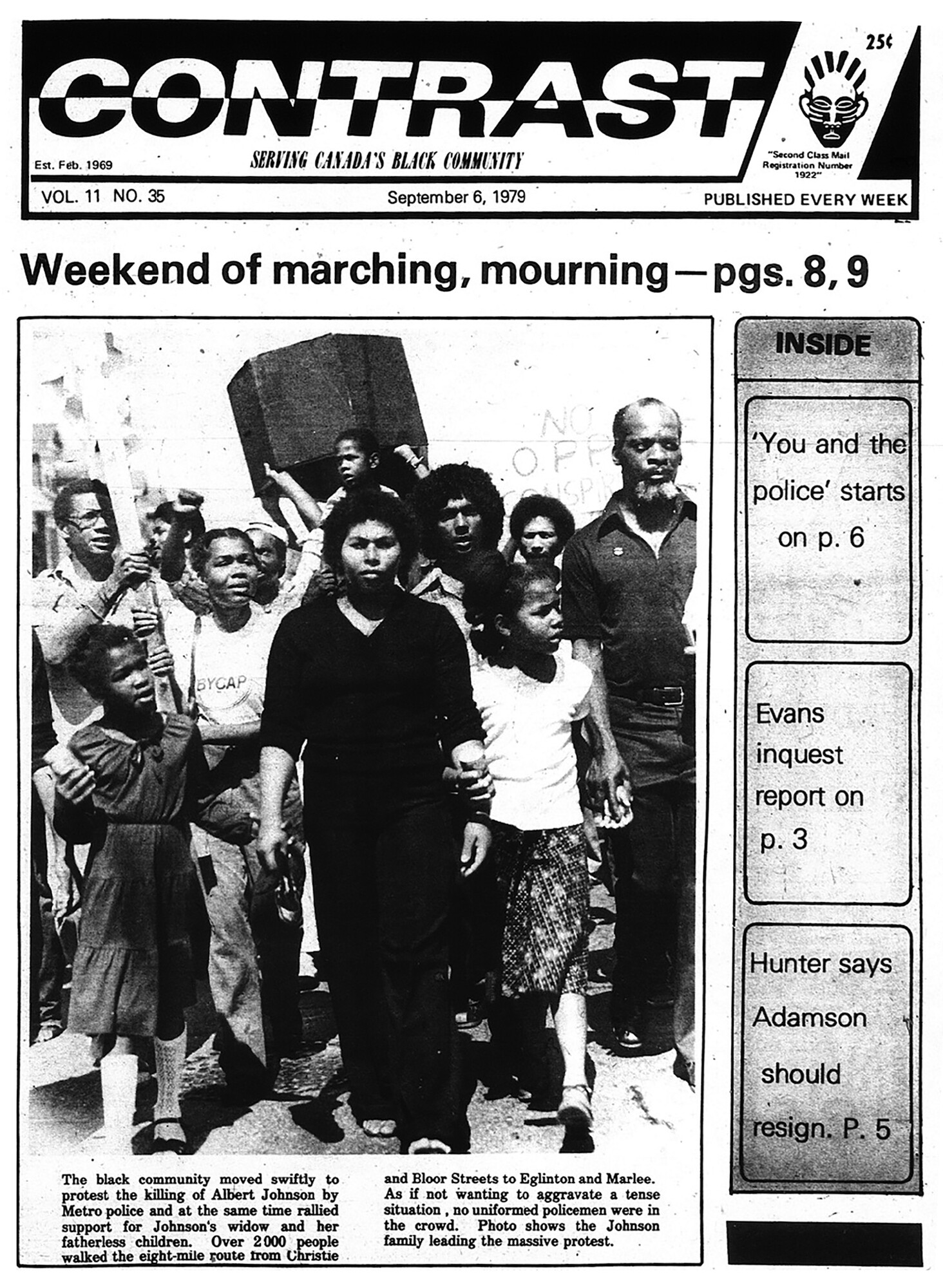

The collective was part of several groups that joined the Women’s Coalition Against Racism and Police Violence. The BWC sought to address the police shootings of Black community members such as Sophia Cook, Buddy Evans, Michael Wade Lawson and Lester Donaldson as well as overall police violence within communities of Black, Indigenous and people of colour.

Constitution of the Black Women’s Collective, March 1988. Courtesy of The Black Women’s Collective & Rise Up! Feminist Digital Archive.

Our Lives Newspaper

Our Lives newspaper (1986-1989) was created for and by Black women.

Born out of the need for a newspaper that documented the lives of Black women in Canada, Our Lives newspaper was created by the Black Women’s Collective in 1986. The publication followed an intersectional framework when discussing the lives of Black women and explored topics such as racism, sexism, classism and more.

The newspaper included various Canadian feminist poets, activists and writers in the Greater Toronto Area as well as those across Canada. Dionne Brand, a Toronto-based poet and novelist was featured in the newspaper, as well as Dr. Afua Cooper, a historian, professor, and poet.

Our Lives documented various campaigns, events and protests led by Black feminists and BWC. Our Lives reported on Ba-Thari Day, organized by the BWC in 1987 as well as an event held by the collective, “Sisters in Struggle – Building a Global Movement” in February 1988, which had Angela Davis (feminist political activist, author and professor) as a keynote speaker.

I am a feminist and a Black woman. I want to make that clear from the beginning. In a nutshell, feminism means for me, self determination, women’s self determination. Because generally speaking, women are oppressed simply because they are women. For us this is compounded by race, class, nationality and so on.

Dr. Afua Cooper, Our Lives Vol.1, Issue 4 – November/December 1986, page 5

Our Lives newspaper, Vol. 3, Issue 1 – Spring 1989. Courtesy of Black Women’s Collective Rise Up! Feminist Digital Archive.

Sisters in the Struggle Film

The film Sisters in the Struggle featured discussion about personal struggles, racism, sexism, and systemic discrimination from the Black Women’s Collective as well as other Black women passionate about feminist organizing.

Sisters in the Struggle (1991) was directed by Dionne Brand and Ginny Stikeman and produced by Studio D, the women’s unit of the National Film Board of Canada. Members of the Black Women’s Collective are seen engaging in an open discussion about Black women and intersectionality, in regard to race, class, gender, sexuality and more.

Viewers get a glimpse of organizing done by the Black Women’s Collective and overall collective feminist action in Toronto throughout the late 1980s . Clips are shown of BWC members outside of Bathurst Station getting signatures for a petition to end police violence. Viewers also see BWC actively protesting with other groups led by women of colour within the Coalition Against Racism and Police Violence.

The film stresses the importance of Black women being involved with the Black liberation and women’s movement collectively. During their discussion, members of the BWC mention that within both fights against racism and feminism, Black women must take up space in order to voice their issues since this space is not always provided.

Sisters in the Struggle film still, Dionne Brand and Ginny Stikeman, 1991. Courtesy of NFB.

Here I am…I’m a Black feminist, I’m a Black woman, and I’ve made a conscious political decision to fight against you know, these certain things that are impacting upon my life and other Black women’s lives, be that racism, sexism, homophobia, elitism, ageism, the whole thing.

Dionne Falconer, Black Women’s Collective, Sisters in the Struggle (1991)

Archiving Black Feminist History

The act of archiving material focused on intersectional feminism helps to counteract a longstanding erasure of Black history not only Toronto, but Canada as well.

The Black Women’s Collective and The Congress of Black Women actively promoted intersectionality in their work. Their advocacy tackled the multiple forms of oppression faced by Black women and helped to pave a pathway with other groups for future intersectional activism in Toronto in the BIPOC and 2SLGBTQIA+ communities.

Canadian archival spaces have maintained the history of the work of Black feminist activism in Toronto. Rise Up! Feminist Digital Archive holds material relating to feminist activism in Canada from the 1970s to the 1990s. The archive holds documents of the Black Women’s Collective as well as both national and local documents for the Congress of Black Women.

The Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collections at York University also has holdings relating to The Congress of Black Women. In 2007, The Honourable Dr. Jean Augustine donated a significant amount of items (including her button collection) to the archive pertaining to the CBWC and her advocacy with women’s rights.

The Archives of Ontario also has holdings of the Toronto chapter of the Congress of Black Women. The Congress of Black Women of Canada Toronto Chapter fonds (F 4656) contains administrative documents such as meeting minutes, event info, a plaque and their constitution and mission statement.

Black feminist history within Toronto’s archives helps to eliminate the erasure of the history of Black women in not only Toronto, but Canada. Archiving Black feminist history also helps to exhibit the history of the everyday lives of Black women and their organizing, and allows us to recognize the importance of intersectionality, community, and preservation.

Sponsor

References and Further Resources

- Adewunmi, Bim. “Kimberlé Crenshaw on Intersectionality: ‘I wanted to come up with an everyday metaphor that anyone could use,’” The New Statesman, April 2, 2014.

- Black Women’s Collective. “Black Women’s Collective – Ba thari Celebration Poster (Toronto) – May 1987,” “Constitution of the Black Women’s Collective – March 1988,”“The Proposal to March 8th Coalition for 1989 IWD Theme “Women and Poverty” (Toronto).” Rise Up! Feminist Digital Archive. Accessed November 25, 2023.

- Brand, Dionne & Ginny Stikeman. Sisters in the Struggle. Montreal: National Film Board of Canada, 1991.

- Canadian Women’s Foundation. “The Facts about Intersectional Feminism in Canada.” Accessed November 25, 2023.

- Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collections. “Congress of Black Women Canada: The Jean Augustine Political Button Collection.” Accessed November 25, 2023.

- National Congress of Black Women (Toronto Chapter). “Congress of Black Women of Canada Toronto Chapter Information Brochures.” Rise Up! Feminist Digital Archive. Accessed November 25, 2023.

- Rise Up! Feminist Digital Archive. “Black Women’s Collective,” “Our Lives: Canada’s First Black Women’s Newspaper.” Accessed November 25-26, 2023.

- Thompson, Charis Newton. “Congress of Black Women of Canada (CBWC) / Congrès des femmes noires du Canada.” Rise Up! Feminist Digital Archive. 2016.